Synopsis

The Conservator of the Trade and Maritime Museum depicts old boatbuilding, like his grandfather Niels Christian Nielsen started on Fejø in 1878, and is still practiced in the family. He gives a biographical sketch of his grandfather and his father and tells about the eel drifters built by his grandfather on Fejø. By weaving in many cultural-historical features, he tells about the traditions and customs of boat building, and a little about the eel fishing tackle and the influence of the German drifters.

Introduction

My grandfather, boatman Niels Christian Nielsen, was born on Fejø on January 30, 1851 as the son of Niels and Karen Andersen. The father, Niels Andersen, who was a tailor and journeyman miller, was born in Branderslev of Nakskov. He had been in private school in Nakskov before coming to Fejø as a miller at the farm of Mads Poulsen, in Østerby. Here he met his wife, Karen Henriksdatter, who was from Fejø . They got married and settled in Østerby, where he worked as a tailor. In the marriage there were four children: Dorthea, Hans Henrik, Rasmus and Niels Christian (who was called Christian). The children spent their childhood at Fejø and were raised to help on the farms, to earn a living for the home.

In Shipbuilding

Grandfather came when he had been confirmed as a carpenter’s apprentice in Karrebæk by Karrebæksminde. His parents had been told by some skippers that there was an apprenticeship there. Between Fejø and Karrebæksminde there was a fairly lively connection, as in the summer a number of skippers sailed with goods between the two places; there was some trade in cattle and what else the island could export, as well

imports of bricks and other coarse goods.

Christian’s mother made sure that his clothes and other necessities were in order, and admonished him to honesty, good manners, cleanliness, and courtesy, and also put him in mind that if a wood chip fell on his ax, he should strop it, as it might otherwise chop badly. With these admonitions he then set off with one of the boats that were going to Karrebæksminde. It was in the summer of 1865.

His master was shipbuilder L. Hansen, and the shipyard was between Karrebæk and Karrebæksminde. Beside this was also a little farm with a plot of land, some pigs and cows and a horse. The horse was also used outside agriculture when they had errands in Næstved for shipbuilding materials. On one of his first trips, where grandfather had to pick up boards in “Trælasten” in Næstved, he had a small accident. When he was going home the load slowly shifted without him noticing until it was too late. A few boards had slipped forward and had hit the horse, so it got scared and ran wild. The boards began to lean out to all sides, and before he could get the horse and carriage stopped, all the boards had slipped off the carriage on a few pieces near, which together formed a windmill. He had get all the boards picked up and loaded on the wagon again, and it was late before he got home. But these are the accidents that are needed to give young people experience.

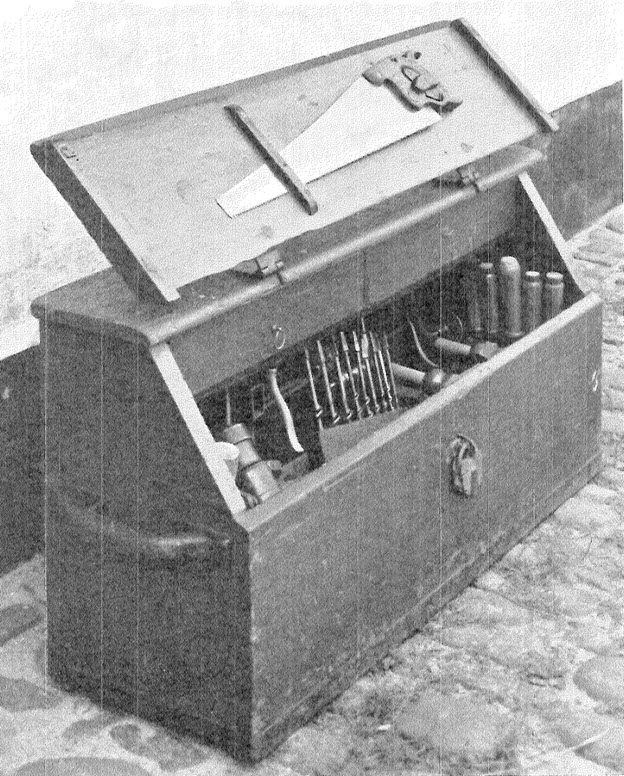

On the square, schooners and yachts were built as well as, when there was less work, small dinghies and tenders. In the winter and during the less busy time, grandfather also had to take a hand in the agriculture, since he lived with the master. He also occasionally had time to make some tools: planers, wooden angles, axes, hammers; the blacksmith forged ax heads, hammer heads, caulking iron, etc. for him. He also got wood for a carpenter’s tool chest and made one for himself. It is a tradition that has held true; even to this day, a ship carpenter’s apprentice gets wood for his carpenter’s tool chest. Yes, even at the iron shipyards, it was customary all the way up to the 1930s that one of the last weeks of the apprenticeship one would get wood for their carpentry tool chest, which they then had to make during working hours. It was almost perceived as a kind of journeyman’s piece before it became mandatory to take a journeyman’s test. Grandfather’s carpenter’s tool chest followed him throughout his life, and it is still intact and in use today. I got it in 1930 from my grandmother when I was 16 and was in apprenticeship.

Shipwright’s Chest

The dimensions of the chest may vary slightly. My grandfather’s chest was small. The length is usually between 40 and 48 inches, the width between 12 and 15 inches and the height between 20 and 25 inches.

The chest had, and almost still has, the shape of a bureau with a sloping flap, but the lid had hinges at the top of the chest so it could be opened. The special shape was probably due to the fact that the chest often had to stand in the open air during the work and therefore wanted to be watertight, so that no rainwater came to the tool and destroyed it. The chest should be able to follow the shipwright throughout life. It was usually made of 1 inch and 1-1/4 inch wood – pine or in some cases oak – as it, when packed with tools, was quite heavy. In larger places, it could also be exposed to harsh traffic, because equal consideration was not always given there.

The chest was preferably made so that the top piece went over the lid, the side pieces and the backing. The lid went over the side and long pieces. At the ends of the lid there were reefs (cross strips) to cover for slag water. The hinges were long leaf hinges (chest hinges); the old ones were hand-forged. On the lid in the middle of the chest there was an fitting for a padlock. Under the bottom of the chest there was a lip on the front and back edge to keep the chest a little above the ground, so that the bottom did not have to stand directly on it and take moisture. On both end pieces there was a handle, carved in wood, so that one could move the chest.

Usually the chest was painted green or brown with black handles and fittings. The bottom grooves and the bottom outside were coal tarred.

Under the top, the chest was equipped with a shelf with two drawers for small tools: ruler, pencil, chalk, chalk line, plumb bob, dividers, mandrel, “rat tail” (small jigsaw) and a scraper (a draw plate for erasing planing strokes). Furthermore, an 8-point divider, seam reamer (a hook for tearing up old work in the seams), record book – usually firmly bound with private records within the margins, hawk’s beak (scribing instrument), chisels, etc. In the lid there was a bracket for “foxtail” (larger jigsaw); at both ends , in the gables, a bracket for chisels, gouges, and drill bits; on the rear, brackets for angles, gauges, spoke shaves, screwdrivers and single caulking iron, as well as a pair of brackets for drill braces. On the front of the chest there was a hanger for hand axe and turning tools. All the fittings were made of wood. At the bottom were planers, bone axes, adze, pliers, caulking mallet, hammers, hand maul, crowbars, chain strap and other rough tools. From ancient times it has been a custom, and still is, that a shipwright must keep all his tools with him. On the site, on the other hand, there are large screw clamps, various bolt drills, bolt pullers, anvils and the like.

The carpenters’ chests were always somewhat personal, which is why it was seldom necessary to provide them with incised or painted names or initials.

Of course, the same chest was also used if the owner mustered as a carpenter in shipping.

Incidentally, this type of ship carpenter’s chest is very old. It is thus depicted in Åke Classon Rålamb: Skepsbyggerij (Stockholm

1691).

On Fejø after the apprenticeship

After finishing his apprenticeship and when there was a shortage of work in the shipyard in December, grandfather went home again to Fejø. It was in 1870. As the journey took place on the apostles’ horses, he reached Masnedsund on the first day, from Karrebæksminde. Here he knew that the customs boat was laid up. This customs boat had its patrol area in the Småland Sea and the southern Great Belt with a station sheltered by Rågø. It was often laid up in December, de-rigged, cleaned and emptied of the ballast so that the people could come home for Christmas; in March it was rigged and made ready, and the ballast irons were coated with anti-rust paint and stowed so that it could be at the station in April. Grandfather knew one of the sailors was from Fejø, and he also got some food and night lodging on the cruiser. The next day he then continued over to Gåbense, probably with the sailing ferry, and home to Fejø.

He now lived with his parents and during that time he took on various repair work, along with building a few dinghies and some small barges. As this construction happened without drawings and by eye, he had some misfortune with his first barge. When he had made the bottom and put the first two strakes on, he could see that it did not have the right shape to be a good barge. He then resolutely put a new bottom in the barge higher up and got it as he had wanted it. He used the first bottom for another barge, and he managed to give it the desired shape, so both barges were good. It was not possible to afford to discard anything, as the price for a barge of 10 to 12 feet was 18 to 20 rigsdaler.

Grandfather also made several repairs to the various vessels in the vicinity. Among other things, an older dinghy on Rågø got new planking. Here he had also almost come across an accident, which he, however, had averted in time. The fisherman had bought planking boards in Nakskov, and in order for them to be easier to bend in shape on the dinghy, they had to be put in water for half a day. There was a bog at the workplace, so the boards were thrown into it, but it as a result, they quickly curved and became hollow, as they only got wet on one side. Happily, Grandpa saw it when he came down in the evening to look at them. He then grabbed some stones, which he laid on the boards so they would sink and get wet all over. They corrected themselves so that they became usable, and the work on the dinghy became neat and satisfying.

Another major repair was the refurbishment of a smaller boat in Lirne (Korslunde parish, Northwest Lolland). It had become very neglected and needed to be caulked everywhere outside. As it was clinker-built, it was a little difficult to get to in the “lands” or “laps” (between the hull planks), and grandfather and the fisherman then resolutely dug a hole in the sand under one side of the boat and overturned it, so as to get to the bottom. This made it easier to get to caulk and pitch it and the stream now also ran better into the seams.

It was common for young boat builders to go out to the fishermen and boat owners for the first time and carry out the repair work on site. Many times they even built small fishing boats with the fishermen, who bought the materials themselves. The boat builders meanwhile lived with the fisherman and received an appropriate payment for their work. Often they would sit in the evening and cut treenails for planking and frames to save on nails and clinch nails. Incidentally, this home-boatyard was used right up until the turn of the century at Nordenhuse on Funen. In this way, the boat builders also became known in the area and could later establish themselves with their own workshop and home when they started a family.

On long voyages

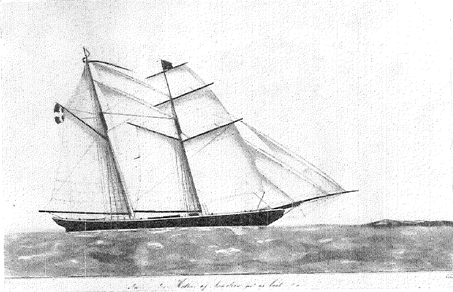

There was no shortage of work for grandfather, but when in the spring of 1872 he was offered a job as a carpenter on the clipper schooner “Hother” by Nakskov, so he agreed. The schooner measured 82 lasts (142.74 tons) and belonged to the company Puggaard & Hage in Nakskov, which was led by skipper JPC Hansen (called “Hother-Hansen”). The helmsman was from Fejø; it was he who had procured grandfather the hire. There were five-man crew on the schooner: skipper, helmsman, carpenter, a sailor and a boy. The rent for the carpenter was 22 rdlr. per month, and the journey lasted from March 18 to June 22

– Colored drawing, signed Lund, on Lolland-Falsters Stiftsmuseum, Maribo.

Before leaving, grandfather purchased wooden soled boots, oilcloth, etc., for a total of 22 rdlr., which he received in advance. The trip went to Brazil for sugar, and it was his first trip across the North Sea. There they also had their first storm, so the schooner was swamped several times. Grandpa’s boots were filled with water, and each time he took them off and poured the water out. When the helmsman had seen this a few times, he said: “Christian, do you think you can heat the whole North Sea? You better keep the water you have in your boots and just warm it up! “It was good advice, after all, and it was also followed the rest of the time Grandpa sailed.

On the way out, the schooner called at Antwerp, where Grandpa supplemented his tools for an expense of 20 francs. He also sent two letters home, which cost 80 centimer in postage. These were the only letters he had the opportunity to write along the way. The total expenses in Antwerp amounted to 7 rdlr in Danish currency. 34 skill, and the money he got in advance

The voyage went without incident to Brazil, but the navigation had cheated them somewhat, because when they came to the latitude of the port of call, they were against the calculation another 2-1/2 days at sea and then had to sail far west in. But this was a common offense at the time , since you did not have such good watches that you could calculate the length [of time] exactly. The schooner now had to run far up a river to a small place where the sugar was cheap because only a few ships could get up there. The sugar was packed in wooden chests, and to get the load stowed full, many of the chests had to be cut down and new ends inserted. This gave a lot of work to the carpenter, and it was also one of the reasons why the schooner had one with him. The loading went well and they sailed away again.

On the way home they visited Newcastle, where grandfather again bought tools, for a total of 10 shillings (= 4 rdlr. 50 shillings. Danish). From there they sailed to Malmö, where the sugar cargo was unloaded, and from here grandfather sent the third letter home. Upon arrival in Nakskov, the trip had lasted 3 months and 4 days. It had proceeded without accident and had brought in grandfather 68 rdl. 90 skill. At the settlement, there was a balance of 24 rdl. 88 skill, when the advances, for clothes and postage as well as for the purchase of tools had been deducted. His settlement book still exists.

Grandfather then continued to sail the following years as a carpenter, as a young man at the time was not really counted if he had not sailed on long voyages. However, he mostly hired on steamships, which at the time had a fairly long voyage, and mostly in North and Baltic shipping. During that period, he manufactured various tools: long planers, angles and bevel gage and also made a little sailor craftwork, including a model of a Newfoundland schooner and a modern clipper ship. However, he only completely finished the models after he came home to Fejø.

1874 was grandfather to war. He was on board the frigate “Jylland” and was, as an experienced sailor, on King Christian IX’s voyage to Iceland with the frigate.

After his service he continued again in the North and Baltic shipping, but after sailing a few more years, in 1877 he went to Fejø to begin his own boatyard there. During his sailing time he had saved a little money to settle down, and as mentioned, he had acquired most of the tools a long time ago.

As a boat builder on Fejø

During the winter of 1877-78, when he lived with his parents, he acquired a small piece of meadow in Østerby down by Dybvig. Here he built a half-timbered house with a tile roof, 21-1/2 x 37 feet in size. At the west end there was a workshop, 21-1/2 x 14-1/2 feet, with a gate on the south side. In 1878 he was granted citizenship as a boat builder. Femø, Fejø, and Askø constituted a ‘birk‘, and the birk court, where the citizenship certificate was issued, was on Fejø. Grandpa also made some rough tools for himself: bucks, saw bucks, a carpenter’s bench, a workbench (or tool bench) with a vice on the right side and on the left side a large wooden vise with a C-clamp as a spindle, a pair of large C-clamps, chain straps, a pair of large pliers, just as he had made himself some wedges, cleats, clamps and other needy tools. He also built a steam box; it was located inside the workshop and the heating device was simply the boiler in the laundry room next door.

Grandpa now immediately set about building and doing repair work. At that time there was no harbor on Fejø, only a small bridgehead, a couple of stone arms [a breakwater?] and 4 gabions, one of which could be used for overturning for keel hauling of smaller boats and yachts. Of the larger new buildings, three dinghies to Vejrø can be mentioned. One was built as a mail dinghy and was in use until 1910. All three dinghies were built without drawings and they were completely his own type. They were good sailors. According to the construction of the time, they had upright stem, but a beautifully framed stern, round-buttocks and with a inwardly curved sternpost, frankly an easy and neat way to get a little round stern in the deck. Some 18-foot pond dinghies were also built, a pilot dinghy for pilot Spender, Masnedø, a smaller dinghy for the fishing control vessel “Falken” in 1890 at a price of 225 kroner, and in 1891 and 93 he built a couple of smaller boats of about 25 feet. These boats had a fine shape and to a certain extent had the new cruiser yachts, which “master” EC Benzon in Nykøbing F. had constructed as a model. They were built with a submerged round stem, beautifully protruding fore and aft and with a round and full deck plan. They were good sailors and became a model for the later known Fejø type, and also for the Fejø eel drifters. All these boats and dinghies were built according to templates and without drawings, but according to sight and experience.

When the harbor in Fejø was built in 1882, there must have been good work in the boatyard, as grandfather did not participate in the actual harbor work, but only when a bridge hammer was to be laid. The work was led by a wheelwright and a carpenter Chr. Olsen, but when they had to straighten the poles into the hammer, and these did not stand quite as they should, they did not know how to approach the matter, and then got grandfather to help them with this work.

After a few years of engagement, my grandfather married on 17 May 1885 to Rasmine Margrethe Rasmussen, who was born on Fejø 2 Dec. 1862. There was still plenty of work, and he must also have had some profit, for the following year he bought a piece of land north of the place he already had. The plot of land measured 59-3/4 x 123-1/2 feet. To the plot belonged a road, approx. 309 feet long and 12-1/4 feet wide, which led to the public municipal road. In the summer of 1886 he moved the house up to the new plot of land, partly because the house in the old square had been rather low, so that at high tide there could be water on the floor, partly because he could get a timber place in front of the workshop. To help with the relocation work, he had a young man, Chr. Mortensen, who also during busy periods had helped him with other work, as well as the mentioned carpenter Chr. Olsen, who was in charge of the harbor work in 1882. They first laid a boulder plot of hewn stone, where the house was to stand, after which it was taken down and re-erected on the new plot. It did not cause any difficulties, as the house was made of timber, but some of the bricks were damaged after all, and these were therefore used in the north side and in the west gable, which was then whitewashed, while the south side and east gable were in yellow stone and oak timber. Simultaneously with the move, the work site at the western end was extended by 7-1/4 feet to the south in a width of 14-1/2 feet. The steam chest was moved and set up along the road; it got an open fireplace where you could burn with old firewood. For the sake of the fire hazard, it was good that it was located some distance from the workshop. Here it still has its place.

In the following years, there was a lot of work in the harbor to careen the yachts and schooners belonging to the island, and vessels also came from the surrounding berths Bandholm and Kragenæs. In order to help in the busy time, grandfather had a house carpenter Rasmus Jørgensen and the mentioned young Christian Mortensen. He also had some work on Skalø (at the west end of Fejø) with fisherman Rasmus Nielsen. It turned into a long day when he worked there. He had an 1-1/2 hour walk to and from Skalø morning and evening, and when the working hours were from kl. 6 am to noon. 6 pm (with a dinner break) it was late before he could get home. He had to get up early in the morning to be at work at 6 o’clock. But that was the working conditions at that time.

In 1892, grandfather built a hand dredge for Fejø harbor. It was built on a daily wage from June to September, and it took 61 days to 10 hours for a daily wage of 3 kroner. The dredge had a size of 24 feet long, 10-1 / 2 feet wide and 1 foot 8 inches high. It was built of pine with ends of 2 inch planks, bolted together, 3 inch bottom and 5/4 inch clinker planking. It did its fullest until up in the 1930s.

Of other special vessels that were built, some ice dinghies can be mentioned to the ferry places Fejø and Kragenæs (the ferrymen Ole Larsen and Ole Bjørn), at 18 feet; two smaller ice dinghies to the county, one to Vejrø and one to Lilleø (Askø municipality), both intended for medical transport in the winter; later similar ice dinghies to the pilot series on Femø and Rågø. According to experts, these ice dinghies were easier to work with than, for example, those at the Great Belt crossing, and they are still used today at the Rågø and Guldborg pilotages (Femø pilotage was transferred to Guldborg around 1930).

It seems like there has been enough orders, but little profit for Grandpa. The small skippers he worked for could apparently earn more than he with less effort. Therefore, on May 7, 1894, after mature consideration, he bought a small clipper schooner “Niels” of 12 lasts (19 tons) from the company Qvade in Bandholm. It was built in Sakskøbing in 1861 and was rigged with a pole mast for a mainmast and with a topmast on the foremast. He knew the schooner very well, as he had had it for keel hauling and repair for several years. The price was DKK 1,600. He changed its name to the schooner “Dyvia” of Fejø.

At the same time, however, something happened that completely overturned his plans to sail with it. In the winter, he had built his first eel drifter, which was handed over on 19 April 1894 in a rig-ready condition to fisherman Frits Nielsen in Karrebæk. It was 25 feet between the stem and stern post, 9 feet wide and 3 feet 8 inches high, and the price was DKK 400. When immediately after the delivery he received an order for a similar eel drifter for fisherman Christiansen in Karrebæksminde, he had until 14 May 1894, a week after the purchase of the schooner, to inform the insurance company that he would store it indefinitely, as he did not expect to go out sailing with it this year. When his brother, Rasmus Nielsen, who lived on Fejø, but in the summer sailed as a helmsman with various Danish schooners on Icelandic fishing, would rather sail as a small skipper, in the autumn of 17 November 1894 he took citizenship as master and then sailed with the schooner. He took it over later, and it got its old name “Niels” again. Rasmus Nielsen had it until 1907, but it was not removed from the register until 1928.

The German eel drifters

The reason why the construction of eel drifters took such a recovery, and that the demand for them became so great that it was possible to get a reasonable price for the work, was that in approximately 1872 the Germans began fishing in Denmark with eel drifters. The reason for this was that in the German waters at Stralsund only a certain number of drifters could fish, and the young fishermen could therefore not start fishing themselves until an old fisherman either stopped or died, if they could not buy the old fishermen out by taking over their drifters. When enterprising fishermen had been informed by the people on the German commercial drifters that the conditions in Denmark at Kallehave, in Smålandsfarvandet and in the Little Belt were very similar to the German ones, they took their drifters up to these places and started fishing for eel. They got many eels – more than the local fishermen took with their hand net, wading net and land dragnet. When the Danes could easily see the advantage of the new fishing, which was also more pleasant and easy, they changed their methods and switched to the Germans. They started buying the imported German drifters, but it did not take long before drifters were built in Kallehave, Kolding and Fredericia, which were copied after the German ones.

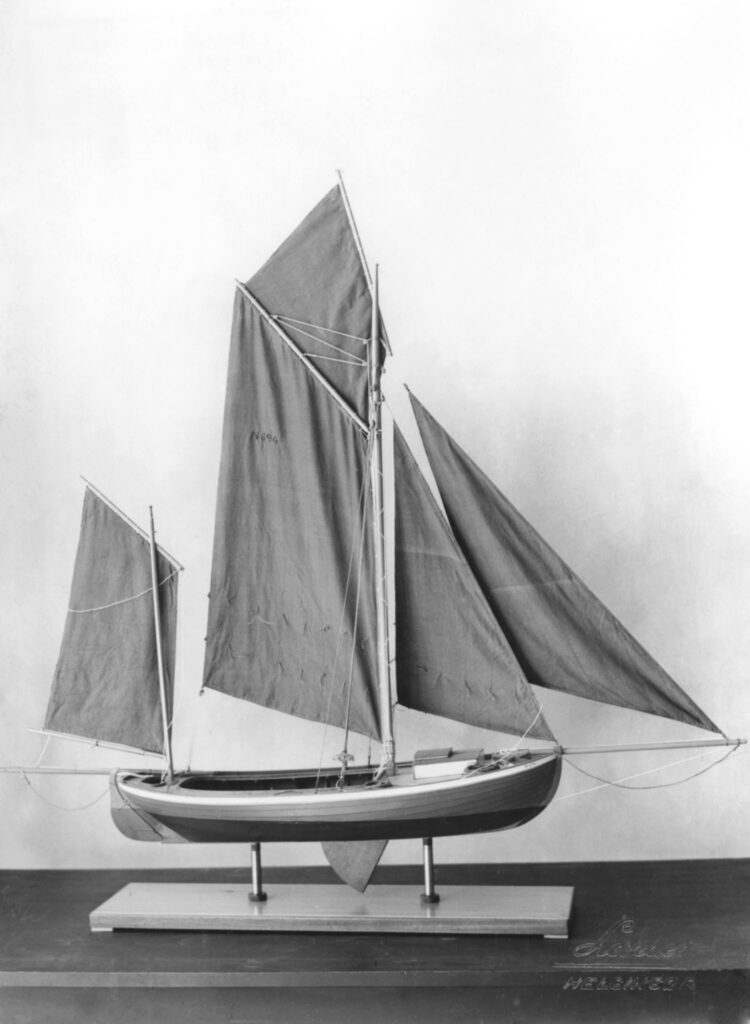

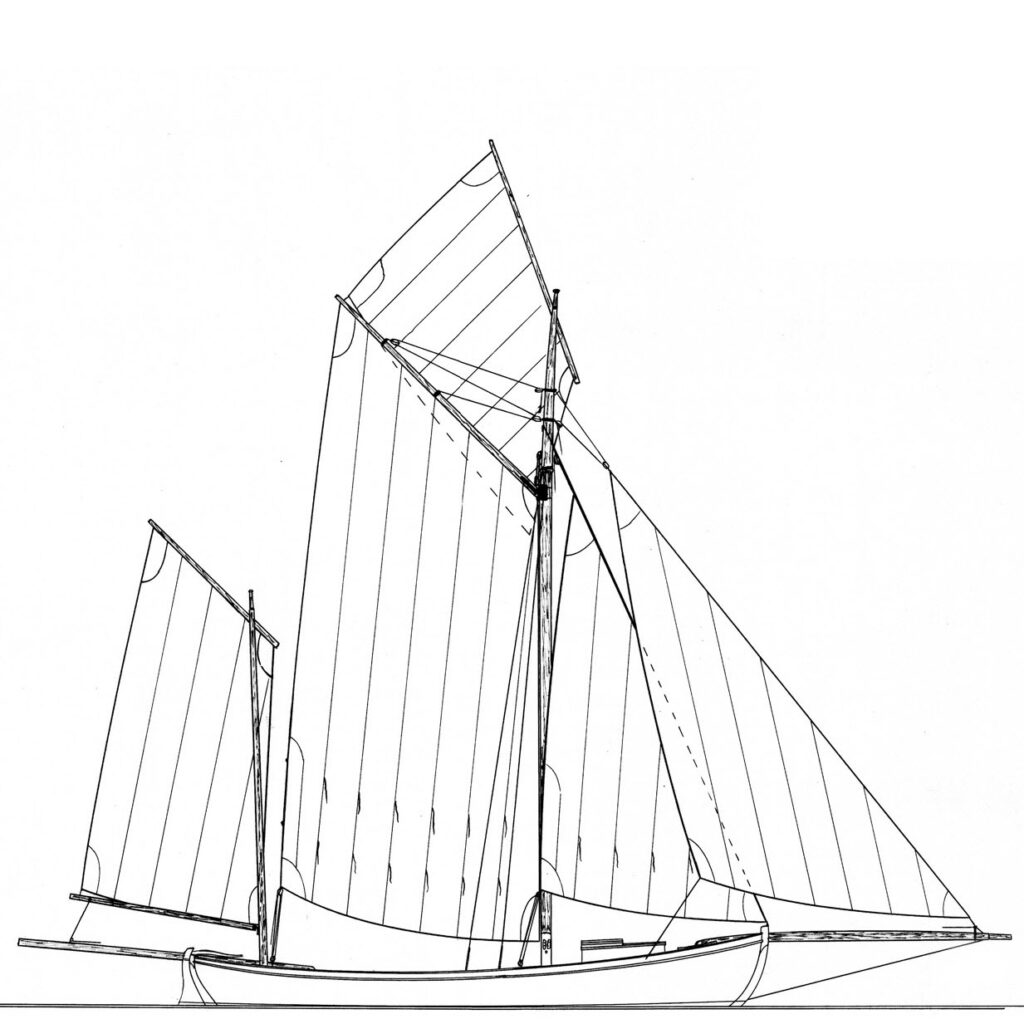

Several of the German fishermen also settled in Denmark, as they had better conditions here than at home, and many also married Danish girls.

The German drifter was approx. 31 feet long between the stem and stern post and was rounded with a rather sharp stern. The slightly more expensive and finer ones had round elliptical sterns. They all had a kind of clipper stem and were fitted with a leeboard (side keel) that could be changed from side to side. The leeboard was necessary so as not to drift sideways, as the drifter had only a slight draft. The drifter was carvel-built with the top plank overlapping. It had front decks with cabin trunk and living space, side decks, and aft an open well for the fish. It was rigged with two masts, jib boom and drift boom, and the sail plan was loose jib, staysail, mainsail without boom, large topsail and loose mizzen.

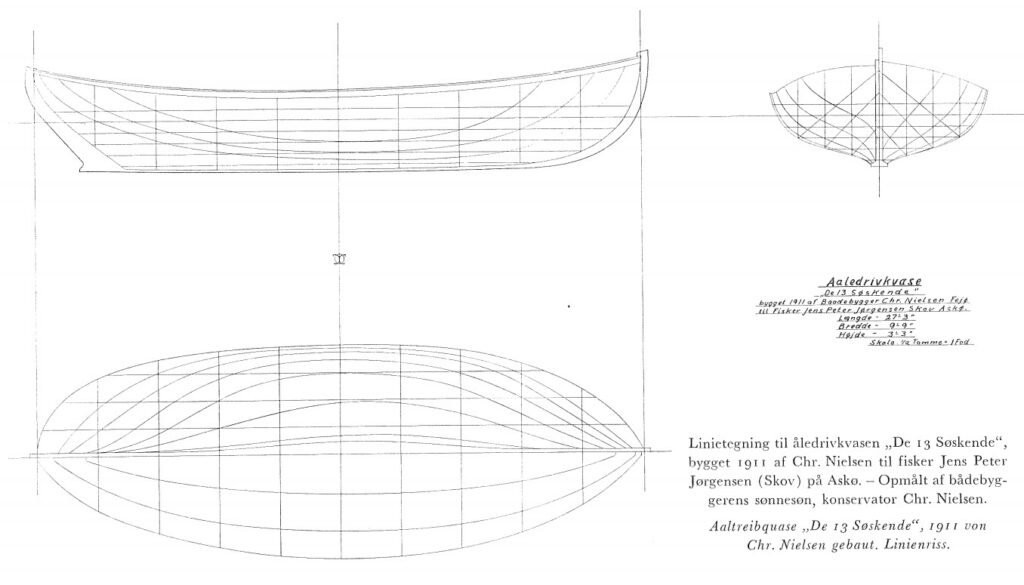

Fejø eel drifters

The first eel drifters were built by my grandfather according to the same templates as his 25-foot boats, except that the bottom plank was cut off. The drifter was then fitted with a plank keel, but instead of the leeboard on the German drifters, it had a centerboard in a groove in the plank keel and he had closed the well with a well deck and trunk. It had the same rigging and sailing plan as the German drifter, just somewhat smaller, adapted to the size of the drifter. Apart from the first two drifters that grandfather built, they were generally 26 to 27 feet between the stem and stern, and he even considered the 27-foot drifter to be the best

This type of drifter was far easier to work with than the German drifter. It was easier to haul up the eel net, and in bad weather it did not work as hard in the sea due to its lighter construction. On the whole, it was more adapted to Danish conditions than the foreign drifters and those built according to the German model in Denmark. It did not take long before the Fejø drifters completely displaced these. Most enterprising fishermen gradually replaced their old drifters and got Fejø drifters instead, and even more German fishermen, other than those living in Denmark, acquired such. Grandfather now had for many years pre-ordered his drifter, especially as the eel fishery was still expanded to other parts of the country, such as the Isefjord and Ringkøbing fjord, as well as Hjerting bay near Esbjerg. Above all came enterprising fishermen from Kolding, who resolutely loaded their drifters on a freight wagon and had them transported by rail across Jutland. In many places, individual drifters were sold, so in this way the Fejø drifters appeared everywhere in Denmark, where eel drift fishing was conducted, with the exception of the Limfjord, where special provisions apply to the vessel length.

From 1896 the shape was almost fixed and only small changes were made. Some were built a little fuller in the middle frame and were experimentally made a little wider, depending on the wishes of the fishermen. Some were provided with an iron centerboard [fixed keel?], some with a centerboard trunk, but they soon switched to using only a wooden centerboard, as this had the most advantages. The iron centerboard often suffered a breakdown if it hit a stone, as it was easily bent, and then was not easy to get up, while the wood centerboard, had the advantage that when it hit a stone, it slid up, after which it fell back into place, when the stone was passed. It also acted like a good leadsman, lifting when it reached the bottom, so that it could warn when the drifter entered shallow water before taking the bottom. The first centerboards were a quarter circle of 4 feet 3 inches in radius, but when it turned out that the drifters accelerated better when the centerboard was not completely down, they switched to making the centerboard 18 inches below the said quarter circle.

The boat building on Fejø was now going well, and in those years Grandma also often had to take a turn at the workshop when it was really busy, both when planking and when the planking had to be riveted. She was a great help to her husband, both in the workshop and at home.

The Materials

Grandpa did not like the space to be completely devoid of materials. Therefore, he always had some oak in logs lying, as well as some Kalmar wood, a particularly good kind of pine, and also iron and nails. When an order was placed for a new drifter, it was immediately calculated according to the previous ones what materials were to be used, so that oak could be ordered in the forest for stem and stern post, keel and frames. The tree came home in logs and was cut and split up on the site. The planking wood, which was made of oak, was either bought in the forest, especially at Torrig and Sakskøbing, and cut at a sawmill, or bought at a sawmill in Sakskøbing in 7/8-inch thickness. The Kalmar wood was delivered from Copenhagen in a thickness of 1-1/4 inches and cut down to 7/8 inches in a planing mill, usually the Carpenters’ Veneer Carving on Nørrebrogade in Copenhagen. The clinch nails and spikes as well as galvanized round nails and drift pins, like the planking boards, were bought from the usual suppliers in Copenhagen. Pine for decks, cabin trunk, cabins and furnishings was delivered by the island’s timber merchant, grocer Holm in Østerby.

The fact that a 3/8-inch board was cut from the bark edge of the Kalmar wood for the cladding was due to the desire to get as good a planking as possible and to avoid that there were wind scratches (small cracks and fissures, caused by drying) in the planking. The cut boards were then either sold to the carpenters on the island or used for small dinghies and barges. Also, what was cut as waste on frames and gunwale could be used for small boats, which is why it was important that such dinghies and barges were built in between the drifters, so that the wood could be fully utilized. When there were good orders, even nails and spikes were bought home in whole chests from Copenhagen. Pitch was ordered in whole barrels, also in Copenhagen. Fittings, mast hoops, parrels for gaffs, rudder fittings, chain plates and anchors were forged in Bandholm or at the island’s own blacksmiths. Grandfather most often used blacksmith Chr. Nail in the old town smithy, which still stands in Østerby.

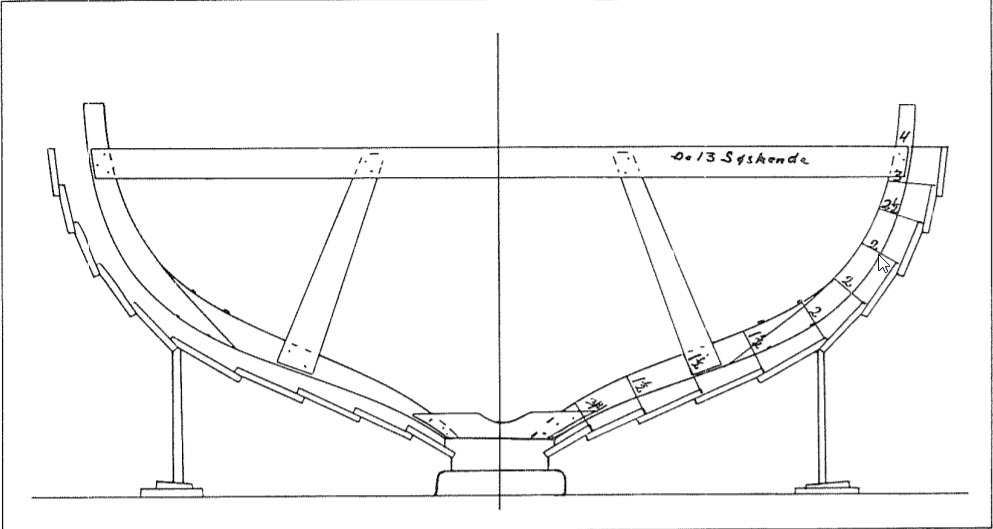

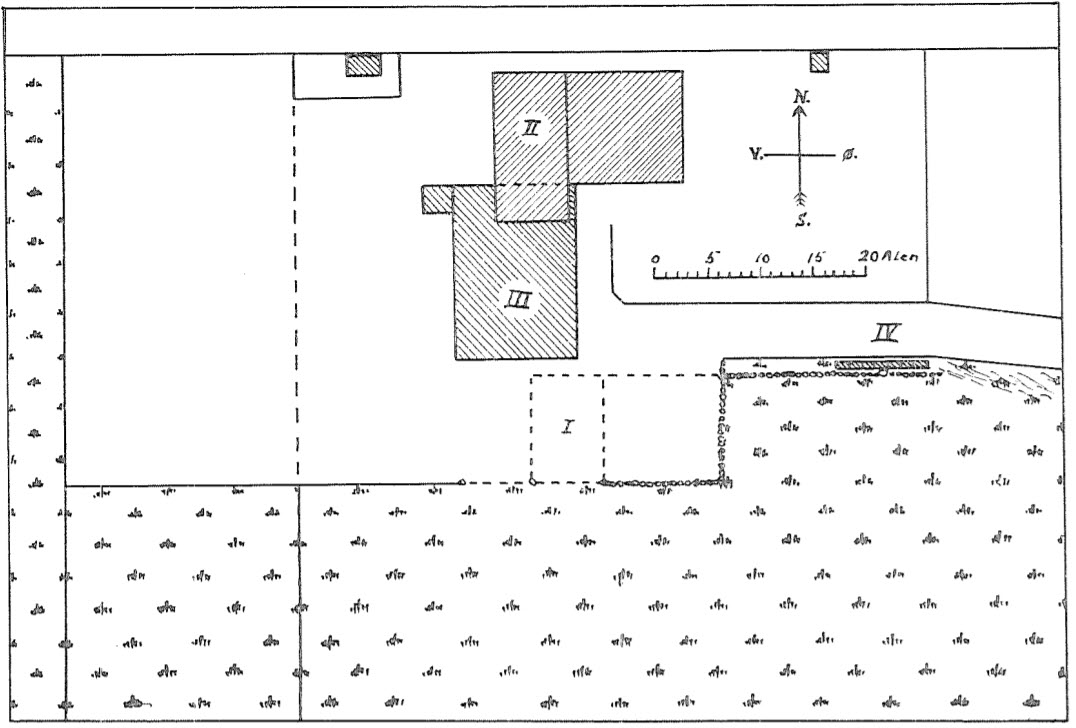

The Building

Now that the keel, stem and stern post and deadwood had been cut and shaped with an ax and planer, they were raised on some bricks in the workshop and supported by up in the ceiling beams. Then 4 templates, made of cut wood, were erected between the stem and stern post with an approximately equal distance between them. These were then stiffened by each other and up into the beams, and then one was ready to begin the planking. This one consisted of 11 strakes on each side. On the templates were inscribed the plank widths and how much distance the cladding should have from the templates. The measurements were taken after the nicest previous drifters. The names of who they were built for were listed, and the lines were often written on the front and back of the template, as well as on the starboard and port sides. It initially gave four different inscriptions, and if it struggled with clarity, different colors could also be used. That way, the same templates could be used for all the drifters, and the fishermen could get the drifter they wanted. The construction according to templates meant that without making special construction drawings, well-dimensioned vessels could be obtained in an easy and safe way.

When the drifter was planked about halfway up, an extra template was inserted at the ends to make it easier to see how much the planking had to change position to get the full and round deck plan. Some consideration had to be given to the wood and its shape during the selection of the planking, and it required a great deal of experience to get a nice plank progression and the right shape of the drifter. Thus, it was important that the curved planks aft took into account that most wood was cut from the upper edge of the plank, so that it could better be so “rich” in the upper edge that it could stretch as much as possible without breaking. Here, therefore, oak often had to be used, as it would be too much risk and work to use Kalmar wood. Some fishermen would also like to have the top and a single plank from the front made of oak. After, where the planks should not be stretched so much, it should be cut out in the middle of the plank, or cut off most of the bottom edge of the plank, so that it does not change shape too much

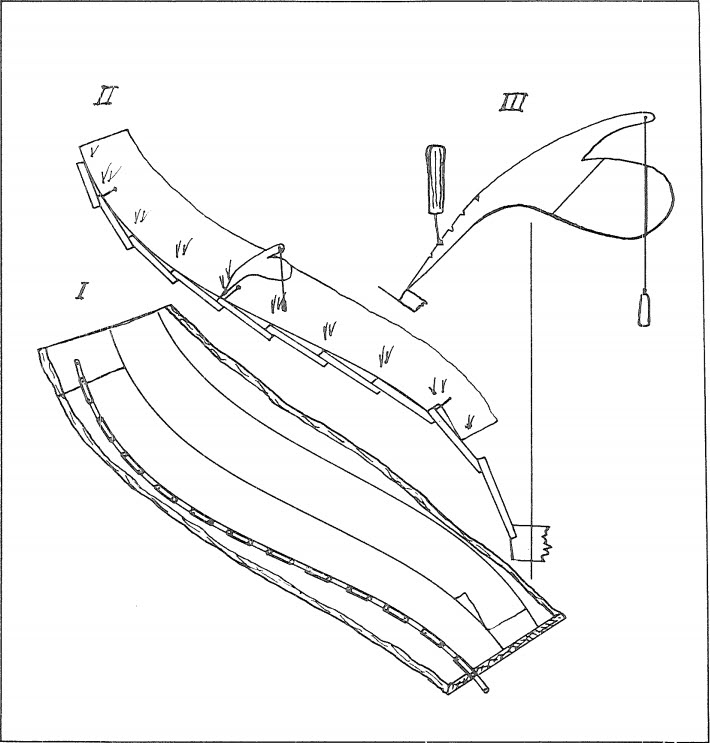

Otherwise, the actual measurement of the hull planks took place with a thin board, approx. 3/8 inch, called a spiling batten, similar to the shape of the plank. Four different battens were used. The battens were bent in the desired shape around the plank, which was attached to the drifter, and a line was then drawn with chalk along the upper edge of the plank on the batten and at the template and in the “neck” (the ends of the plank towards the stem and stern post) written the width of the plank. The batten was then laid on the new plank, and the shape transferred matching the chalk line on the plank. This was then cut and planed and should now be ready to enter the steam box, where it was heated in steam for approx. 45 minutes.

The steam chest was a long box of wood, where the planks lay for steaming on some iron bolts, approx. a third up in the coffin. At the bottom there was only cold water, as the steam condensed and became water. This ran out of the box at the bottom.

When the plank was now suitably “sweated” (steamed), it was removed and could now be bent in the desired shape by means of clamps and wedges in the rabbets at the stem and stern post and along the subordinate plank with clamps and wedges of wood. In several places it was supported by sticks and, where it should change position most, with some special wooden forks which could be lowered over the plank and twisted into the desired shape. The planking was overlapped by about 1-3/8 inch (over the landing or over the “lægget“), and when the plank was formed and landed with the subordinate plank, clinch nails were inserted with a suitable distance of about 5-1/2 inches. Nails were inserted in the rabbets of the stem and stern post. At the butts (the assembly of the planking), butt blocks of approx. 30 inches long to smooth these. Once the drifter was planked, some supports were put under the plank lands, and some nails were also put into the template. It was common practice to treat with “lifted” pancakes (yeast pancakes made from apple slice dough), when the fastening had been done, as it was an important part of the work that had now been completed

Now measurements could be taken of the frames. This was done with a flexible mold (one of small segments riveted together, where the segments alternated between single and double links at each joint; the length of the segments was about 4 inches). The mold was knocked down onto the planking, where the frame should lie, and afterwards it was laid on a piece of wood that had the shape of the frame so that it could be roughly cut and hewn with an ax. The frame wood that was to be used during the day was usually cut and chopped in the evening, as this work did not require as much light as was necessary to engrave the frame. The lighting in the workshop was two or three kerosene lamps. The frame was then fastened to the planking with some nails and placed on it where it was to be used, to be engraved there with two marks in each plank land with a tool used for this purpose, called a hawk’s beak (or monkey), provided with a plumb line and weight. The shape that now emerged was cut with a saw by two men, one on each side of the frame, so that they could see the line. The frame piece was fixed in a clamping device, usually in a work bench

When frames, floors and well bulkheads were nailed to the planking, the templates could be removed, and you could then lay well decks and gunwales, knees and deck beam. A gunwale is a continuous reinforcement of all the planking around the inside, covering the frame ends and bolted to these. Then the bulkheads were inserted and the hatch in the foreship arranged, on which a deck of 1-1/4 inch pine planks were laid. In the beginning drifters were covered with tongue and groove planks, later, when the drifters became a little more expensive, of cut through 1-1/4 x 7 inch planks. Then a forward cabin trunk with sliding cover was placed over the hatch. On the deck, oak frames were placed around the open space amidships and around the cockpit aft. After this the toe rail was made (almost like a waist netting), at the ends towards the stems it was made of oak, but over the middle of one inch pine board, 3-1/2 inch high. The toe rail was bolted into the gunwale with “stub bolts”, in this case 3/8 inch round iron of 5-1/2 inch length, tapered at the lower end, and spitting scuppers were cut in the lower edge of the toe rail against the gunwale. On top of the toe rail was placed a small cap rail, and on the outer upper edge of the upper planking board a semicircular fender strip of oak (“rub rail”), 1-3/4 x 3/4 inch. Here and there was a lowering keel (“centerboard”), rudder and tabernacle, and thus all the woodwork on the drifter was finished.

The arrangement of the drifter was as follows: on the port bow, in the toe rail, a small open fairlead for the anchor; on the deck in front of the cabin trunk a bitt for mooring and for fittings for the loose sprit; the bitt stood 4-1/2 inches to port. The cabin trunk was also shifted 3 inches to port to provide that much more deck space on the starboard side to better accommodate the eel net. Between the cabin trunk and the frame about the open space amidships was placed a mast tabernacle in an oak partner in the deck; the tabernacle rested on a deck beam and on the front edge of the well bulkhead. Aft of the open space was the aft deck with a guide cockpit; in front of the cockpit was the mizzen mast, and on the port side the drift boom and fittings for this. The drift boom was loose and had an oblique position so that its aft end protruded beyond the center line of the drifter.

The interior of the cabin consisted of an enclosed space furthest forward]; up against this under the foredeck was a transverse berth, below the deck on the starboard side a closed berth. The bunks were single berths as the crew consisted of only two men. In the port side stood two fixed cupboards for provisions and clothes. Against cupboards and bunk there was an open bench on each side. Between the benches on the bulkhead below the berth was a folding table with fiddles, which was fastened to the bulkhead with a pair of hinges. Under the deck between the well and the cabin trunk there was a small elevation for the cooking device: a cuddy (galley) stove or a petroleum appliance. The floor was transverse. The toilet conditions were arranged very simply, using the triangle between the drive boom and the ship’s side, where you could sit safely.

Midships, in the open space, was first the well. The two front compartments were the centerboard well, in which the centerboard was placed and supported by an additional reinforcement on the keel; the aft room was for the eels. On the well deck on the starboard side, there was a loose bulkhead for eels and “dung” (seaweed, mud, etc.), so that this would not spread over the entire lower deck. On the stern edge of the well hatchway was a wooden pump with which one could pump into the well the water that came into the drifter, especially during fishing when the contents of the net were plunged onto the well deck. Aft of the well there were transversely planked deck panels; between the cockpit and the space amidships was a bulkhead. In the cockpit was a transversely planked deck panel, and a little down from the deck a small bench on each side.

After the woodwork was completed, the waterline was set, partly according to experience, partly according to the previously built drifters. A horizontal board was placed transversely at the stem and stern post, on which a longitudinal string was pulled. This cord was then pulled in along the upper edge of the board towards the planking, and to support the cord, small pins were inserted where it reached the planking. After these marks, the waterline was then torn [scribed] into the cladding with a small scraper (dividers, if one leg has a scribing point). After this, the drifter was finished so that it could be loosened from the bracing that held it in the construction position, and the stem and stern posts could be cut to their final shape at the top edge.

The drifter was now placed on its side so that it could be caulked in the laps and along the keel and bow. Light yarn or cotton thread was often used for this purpose. After this was inlaid, the seams were stained with wood tar pitch. Fittings were then added: “hourglass” (in hourglass form) between the keel and stem and stern post, rudder fittings and chain plates.

Now the drifter got coal tar at the bottom and was painted. Schweinfurt green was used as the base color on the outside. The deck was usually varnished; the varnish was mixed with some English red. Outside, over the water, the drifter was like painted green with white toe rail; inside on toe rail and gunwale it was green. The cabin trunk was white with a green roof and a green hatch. The drifters that were not painted green on the outside were often gray, and some, especially those on Askø and Lilleø, had brown roofs and hatches, and their decks were also often painted brown.

Sails and masts

The sails were generally ordered from sailmaker F. N. Halmøe in Nykøbing Falster, if the fishermen had no other wishes, but they usually left it to grandfather to order the sails, and he preferred Halmøe. They usually agreed on size and quality. The biggest difference was whether the drifter should have pointed or square topsails. Grandfather set Halmøe very high as a sailmaker, and the sails sewn by him always stood well. After sailing a bit with the new sails, they were often impregnated with a mixture of horse grease, ocher, coal tar and water, which in hot conditions was smeared on the sails.

Now the masts and spars were made. The mast was preferably of a pine beam, 33 feet long and 6 x 6 inches thick, so you could get as stiff a mast as possible. The other spars, sprit, drift boom, topsail yard, gaffs, boom and mizzen mast, were usually made of round spruces. The rigging was two shrouds and a stay, both of twisted iron wire. On the starboard side there was a so-called “dirt tackle” to lift the net in with. The running rope was of hemp or manila. The shroud was connected to the chain plates with lanyards, and the stay often went through a hole in the bow into the bitt or was shackled to a bow iron.

Normal Dress

My grandfather usually wore black leather clogs, blue mole leather trousers, white linen canvas shirt with neckline and half-rolled-up shirt sleeves, so that the wool sweater protruded slightly below the shirt, blue Holmen’s vest and cap with black leather shade and shiny buttons for the chin strap, the so-called “Nykøbing cap”. His underwear was a long, long-sleeved wool sweater and long underpants, home-knitted with two stitches purl and two stitches straight. In the summer he wore socks and in the winter long socks that went up above the knee. They were either black or gray. Apron was never used

When he was in the fine clothes, it was blue Holmen’s cloth: long trousers without openings, two-row, long jacket, vest, large, stiff, white lapel with bow under the points, tuxedo front and on his head a cap. On his feet he wore black shoes or fat leather boots. In the vest pocket sat the watch, fastened to a thin double gold chain, with a medallion in which a photograph of grandmother and a lock of her hair.

The Launch

When the drifter was about to be finished, the fishermen who had ordered them arrived. Those who came from far away had often sewn the money they had to pay for the drifter into their woolen sweater, and they were eager to get rid of the large amount of money as soon as they arrived. They wanted to live with grandfather until the drifter was finished, and since they had seldom paid quite a lot or anything at all in advance, the sum often amounted to 600 to 700 kroner. Grandpa did not like to send announcements for them until he was sure he had the drifter finished. Otherwise, they usually went and came up with so many different little things they would do differently.

Finally, everything was ready for the launch of the drifter. The local fishermen and those of the island’s residents who were interested in ships always knew this a few days in advance.

The drifter was towed from the workshop across the meadow to the northern bulwark in the harbor, from where it was to be launched without skids beyond the bulwark. The whole launch took approx. 2-3 hours. When the drifter had come out of the workshop, a boom was first laid across it and it was tied to the chain plates. A couple of men supported the drifter so that it would not tip over. The boom only protruded to one side, as it had a better sense of whether the drifter kept its balance. A four-cut hoist and some chain were used to pull the drifter, so that the hoist, when it had been hauled to the block, could be “overhauled” (shortened). The drifter was pulled on the keel, and “carvings” were used as joists, i.e., the half-round pieces of wood that had been cut from the sides of the logs that had been cut up into frame wood. They were smeared with green soap (“grease patches”), and the joists were laid at a distance of about 6 feet and were “overhauled” as they became free aft, in order to be transported forward again. There should be 12-14 joists to switch with.

Now that the drifter had arrived at the slipway, a couple of clamps were placed by the keel so that the drifter would not be able to slide sideways. The boom across was lowered and the crew evenly distributed on both sides of the drifter. As a precaution, a sack of shavings was placed on each side of the bridge hammer. Everything was then made ready for the launching, and the end of the fall was fastened to the horse aft to be able to stop the drifter in motion. If there were children, they were allowed to be up in the drifter during the launch. There was now a warning from grandfather, who of course had the leadership of the launch, that everything was clear, and with a brisk grip and push, the drifter was set in motion and then slipped into its proper element. Sometimes cheers were shouted as the boat took to the water, which happened with a cascade of water. Those present wished the owner good luck with his new ship.

The drifter was not adorned, neither with flag nor greenery. No direct christening or naming of it was done either. Had the boat name been determined in advance, this was either painted on or a nameplate was affixed. There was no secrecy of the name in advance, as one with the baptism of larger ships. By the way, a number of drifters never got their name painted on, but they should at least have a name when they were registered with the customs. Before the Fisheries Act of 1888, the boats were rarely registered and were not always given names.

Photo. Ms. Captain Christensen.

The selection of the name took place in different ways. Most drifters were named after the owner’s wife or daughter (e.g., “Rigmor”, “Anna”, “Marie”, “Inger”), or the name was associated with fishing (“Eels”, “Salmon”, “Herring”). The boat’s sailing ability evoked names such as “Gull”, “Swallow”, “Swan”. You could also take the name after larger ships or after warships on which you had served your military service (“Viking”, “Tordenskjold”, “Heimdal”). One of the drifters, “Chr. Nielsen “(1907), was named after grandfather.

When the drifters were sold, they were often renamed. However, there was some superstition with the renaming, so many were afraid to give them a new name. The old owners often wanted their wife’s name not to be worn anymore after they had sold the drifters, so they demanded that they be renamed, and as a rule, they then got the name of the new owner’s wife.

The launching banquet

After the launch, there was a nice launching banquet in the workshop. All the helpers took part. It was never difficult to get crew for the launch. There was a need for 10-12 men, but as a rule the double number showed up. It was free labor, but they were rewarded with being invited to the feast.

In the workshop, the floor was swept when the drifter had come out, and tables and benches were set up. The table was like some planks on a few bucks, and the benches were scaffolding planks on some nail chests.

For the party, coffee, “æbleskiver” and the traditional “Fejø punch” were served. It may amuse readers to get the recipe for this punch:

- 2 pots room to 75 øre,

- 1 A bottle of red wine to 58 øre,

- 2 pounds of sugar to 20 cents,

- whole cinnamon for 10 øre,

- equal parts water and rum.

The expenses for the punch amounted to 3 kroner, which corresponded to a day’s wages, as prices were at the turn of the century.

The mood during the feast was high, and people recounted memories and talked “ship”. Many different topics were discussed. Many believed that ships had both emotion and vision, and they had good intentions with their ship; as mentioned it was usually named after his loved ones to honor both them and the ship. You also want to be good to ship, give it good rope and good sails and keep it neat with paint. It meant something to do well with his ship. Among most old fishermen, there was a firm belief that the ship could see, and many would rather buy a used drifter that had exhibited good fishing qualities, rather than a new one, as they believed that the fishing results could just as well have come from the vessel as from the skill of the fisherman. It had turned out many times that two drifters could lie and fish next to each other, and one got a lot of eels and only a little “dung” (mud, seaweed, etc.), while the other got a lot of “dung”, but no eel. Many times, when they had to haul after a single drive, both eel net and lines could be twisted, so it all looked like a large scarf twisted around. Likewise, it often turned out that when such a neglected vessel changed owner and came to someone who had it painted and gave it new ropes and new sails, it could improve and become a good friend and get to sail and fish like others drifter[s]. It was then a sure proof of the ship’s ability to accept. Because of this superstition, it was easy for the enterprising fishermen to sell their old drifters and have them replaced with new ones. But it was certainly not always that the good reputation of the drifter met expectations when it changed owner.

Likewise, it was of great importance, it was believed that there was money in the ship, and it was quite common to put a coin under the mainmast. When the old masts were replaced, the money that was under them, together with a new coin, was put under the new mast. On older ships, there could thus be many coins under the mast.

Grandpa never built a dinghy or boat without a coin inserted between the stem and keel or between the deadwood and the stem. He did not think it could hurt, and then there was always money on board. Since for many it was of great importance that this coin came in, there was no reason not to follow such a custom. If the builder had the opportunity to be present at the raising, he added the coin himself and could at the same time give a hand in the raising. Otherwise, there was no ceremony on this occasion, other than that he came in and got a cup of coffee. Later, a round of beer was given. Many thought that the coin meant good luck and financially good fishing, and when the fishermen came later on to pick up the drifter and join the launch, they usually asked if there was money on the keel, and grandfather always gave an affirmative answer. This custom of the coin has still been retained in place, and I dare say that no ship has been built without a coin in it.

Portrait photo 1910

The Handover

After the launch, the drifter was rigged. Either the rigging was processed by grandfather or also by an elderly sailor on the island.

Then the drifter was handed over, and if it was within the fishing season, they went fishing immediately to test its fishing properties and sailing ability. One would like to try it with the other drifters and see if it had been given better sailing properties and how the sails stood. It was usually just like the previous ones, but sometimes some improvements were made to the new ones. I do not think that any drifter has ever been built that can be said to have been a “death sailor”.

The drifters were to be registered with customs at the place of residence, where they were measured and entered in the register. If the owners immediately started fishing, they waited with these formalities until they first returned home. Grandfather prepared a handwritten builder’s certificate upon receipt of the money and delivery of the drifter. In all its simplicity, however, this was a legally valid document, and it was also provided with stamps, picked up at the ‘birk‘ court.

The drifter was delivered in rig-ready condition. This concept covered the delivery of the drifter with fittings, masts, and spars, as well as the primer and coal tar at the bottom. The owner, on the other hand, had to provide anchor, sails, navigation equipment, cooking utensils and ropes.

As a test of the wording of the document in question, the drifter ‘birth certificate’, the text of the first person’s builder’s certificate follows:

BUILDER’S CERTIFICATE

Signed boat builder Chr. Nielsen corrects here, by the signatures of two men, to have built the drifter called “The Swallow” and sold it to fisherman Frits Nielsen ready for sale for 400 kroner (writes four hundred kroner). The drifter is built of oak and pine, 25 feet between the stem and stern, 9 feet largest width, 3 feet 8 inches on the midships, and the entire said 400 kroner has been paid to me.

Fejø 19 de april 1894

Eel Net and Eel Fishing

Since the eel fishery was of great importance, especially in Smålandsfarvandet and Lillebælt, and as the drifters designed by grandfather, whose building has just been described, came to play such a big role, it will probably not be without interest to get a brief description of eel fishing.

The hand net was usually driven from two dinghies, where one dinghy was provided with a well and had one line, while the net and the other line were in the other dinghy. After the first had been anchored or fastened to the bottom in some other way, one line was first rowed out with the dinghy that had the net; then this was set, and the last line was given out and rowed up to the first dinghy and then anchored as well, after which the wet in the lines was hauled up to the dinghy. Thus continued throughout the fishery.

The wading net was a net of slightly smaller dimensions and was used only in shallow water. Line and net were waded out, i.e., the fisherman went wading in the water out with the net, sometimes up to the middle of the waist, after which the hand-net was hauled up to the place from which it was set.

The land dragnet was set from the shore, and the procedure was the same as for the hand net, except that only one dinghy was used to set the net, while the hauling work took place from land.

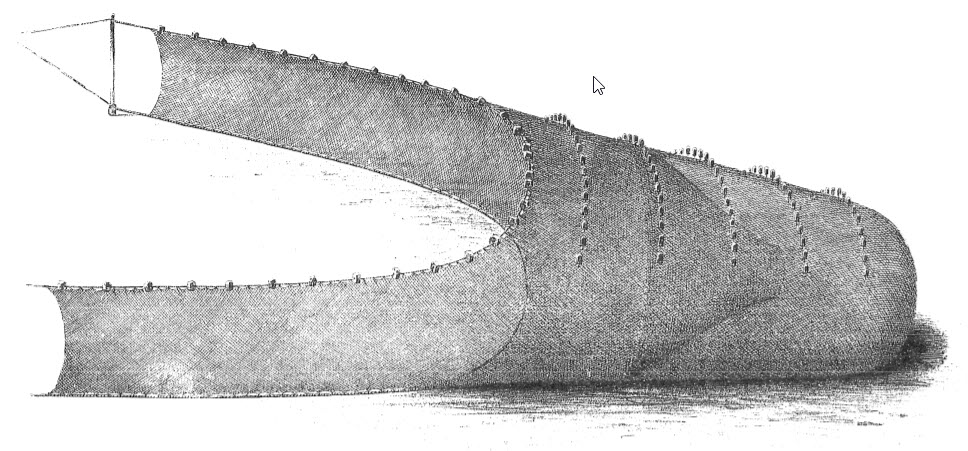

The eel drift net was a tool similar to the previous net, but the use was somewhat different. It was shaped like a sack with arms and with a single funnel to hold on to the eels so that they would not be able to run out of the net when caught. According to C. F. Drechsel: Overview of our Saltwater Fisheries (Copenhagen 1890), page 52, the dimensions of the wetland were:

| Sack length | 16.5′ to 20.6′ |

| arm length | 24.7′ to 28.8′ |

| net depth at entrance | 8.2′ to 9.3′ |

| arm depth at the entrance | 8.2′ |

| arm depth at front end | 6.2′ |

| number of knots in the front part of the sack | 19 to 20 per foot |

| the same, in the rear part of the sack | 21 to 22 per foot |

| the same, in the arm | 18 per foot |

Lithograph from around 1900 in catalog from Fiskenetfabriken Danmark, Helsingør

Fishing with Eel Driftnet

If the fishing was to begin immediately when the fisherman received the drifter from grandfather, he made sure to take the fishing tackle with him from home. He and his wife would usually have made the eel net in the winter prior to the completion of the drifter. They most often bought cotton yarn and knotted and tied the wet themselves and led it on the wet line. This could often have been used and originated from an older wet. Should the net be bought finished, the price was approx. 75-80 DKK, but when they made it themselves, they only had the direct expenses of approx. DKK 20-25 for the materials. If it was an enterprising fisherman, he would usually have an extra net. The coal-tarred nets used at the turn of the century fished best when they were dry; if they were permeated with water, this caused them to become sluggish and unable to stand with the right shape in the water.

From the drifter, the net was played out with lines between its sprit and drift boom. One now imagines the drifter rigged for fishing: the front and aft net line, which were of coir rope (coconut), were made equal in length, and the length was marked on the aft net line, which could be made long or short at will. The front line was provided with a spliced eye that was slid over the end of the sprit, and an inhaul line was attached approx. 4 fathoms from the sprit end, so that one could get the line onto the deck of the drifter. At the stern, a rope was inserted through a hole in the drift boom on the centerline of the drifter, which was led into a cleat on the inner end of the drive boom, and the other was knotted to the net line, where it had the same length as the front line. This line was now hauled to the hole and fastened to the drift boom. There was also a thin line on the stern line, which was led onto the deck so that the net line could be hauled in. The net line had a suitable length according to the length of the drifter between the sprit and the drift boom. Between the two lines the eel drift net was fastened.

Net and line were now on the front deck of the drifter right in front of the shrouds by the mast on the starboard side, as the fishing had to take place from this side, so that the drifter could follow the rules of the sea with the wind in from the starboard side, to have right-of-way over ships that had the wind in from port, having to hold back for it*.

*By mistake, plate XV.A in C. F. Drechsel: Overview of our Saltwater fisheries (Copenhagen 1890) has been mirrored so that the net is shown set from the port side instead of the starboard side. The same is the case in F. Holm-Petersen & Kaj Lund: Høst fra Havet (Odense 1960), p. 150 (top drawing).

They now sailed out to the fishing place, and they positioned themselves so that the drifter could drift partly with the wind. Then the net is given out after first tying the place where the eels were to be taken out and where it was to be cleaned of seaweed, mud and the like. (called “dung”); this was in the back of the net. They now eased the net over the side and made sure that it did not tip over, as it should have the upper side with the cork floats (wood floats) up and the iron weights, usually consisting of 2-3 chain links each, descending. When this was done, you paid out a little of the net line and then tightened a little to see if the net was as it should be. This was not always easy, especially when it was dark at night. Then the rest of the line was released, and fishing could begin.

The smack drifted sideways with the net trailing behind it. Jib and mizzen were preferably set to get as much balance as possible in the sail plan, and the topsail was usually lowered in the lee of the mainsail. It was set again when sailing again to the fishing place. A haul could have different lengths, from 1/2 hour to 1-1/2 hours, depending on the bottom and weather conditions as well as the fish stock. By setting the sails, one could drift in slightly different directions. Drifters could sail a little forward, at the same time as it drifted sideways, or it could drift a little aft. The first was called sailing close-hauled, and the second drifting astern.

When the drift had ended, slack was given to the aft drift line so that the drifter could go to the wind, and now the lines were hauled in front of the shrouds and were shot up on the deck. Then the net was hauled up to the drifter. When the arms and some of the net had come on board, a strap was tied around the last of the net, and it was lifted with a hoist in the rig, called a “dirt tackle”. The eel net’s content of fish and “dung” was then dumped on the well deck, and the fish then had to be sorted. The eels were measured as they must not be under 13 inches. Were they, they were thrown out again. When the net was cleaned of its contents, it was immediately re-released, or one sailed back to the place where the drift had begun.

The eel fishing with drifters could be run hard and was then a slave’s job. The fishing lasted from May to September and took place at night, except during the hot summertime, when it could also happen during the day. At that time, there were many fishermen who virtually did not get sleep. The crew consisted only of the fisherman and a boy (called the “helmsman”). If it became completely still, it could not drift, and when the fisherman laid down on the berth, it was often with the topsail sheet twisted around his wrist, so that he could be awakened when the sail hit the wind and pulled his hand. He then got up to speed and continued fishing. This paid off in the end, as a drifter could usually fish for an amount of 6-700 DKK in a season, while the tenacious fishermen could fish for both 1000 and 1200 DKK. A night with 100 eels was considered very nice, and with an eel price of 35 øre per. pounds, it could give 7 kr., when 5 eels were counted on the pound. In addition, there were eelpout, flatfish and other fish, which came into the net. Many celebrated such a catch by being served thin pancakes.

Those who drifted on the channel edge, which was difficult fishing and required a lot of care with the constant use of beacons and careful navigation, could often get double the catch of eel, in addition to the fact that there were more eelpouts and also could be some flatfish, such as flounder and plaice, and this significantly increased profits – but it also required her manliness, as the net had to constantly go up on the edge of the channel] dropoff and not tumble into the deep. If it did, the whole trawl was wasted.

After the net was released again, the boy could start sorting fish and “dung” on the pond deck. This had to be done before it could be hauled again, so there was plenty to do for both fisherman and boy. Many boys got meals and the money they could earn by sorting butter and shrimp for hook bait. The most enterprising fishermen, on the other hand, gave the boy a fixed salary and a small share in butter and shrimp, as these were for them a fairly large part of the profit. It was a wet and cold job to fish, but it was felt by many as a glorious free life, and the boys considered themselves finer than the comrades who had to go to the farmers. They also had more money in their hands than these, as they had a share in the small fish. By diligence and frugality, they often saved so much together that once they had completed their military service and went to war, they could buy a fishing vessel and start for themselves, often without owing for either the drifter or the gear.

Not all fishermen went fishing in storms, but it was a given that bad weather could often give many eels, especially if it had been quiet and warm for a long time. It was then as if the eels became more loose from the bottom and were easier to catch. But it was hard work to lie outside and fish in the dark and rain. The older fishermen could, from the depth of the water and the nature of the bottom, say where they were; after all, it was impossible to find out where there was land when everything was rumbling dark. When a normal daily wage ashore was only approx. 2.50 to 3.00 DKK, it was good money that came home after strict nights at the fishing spots.

Boatbuilding up to 1917

As the demand for the drifters got bigger and bigger, and there were always pre-orders, there was an opportunity for Grandpa to put a little on the price. As the standard also increased in the competition with the drifters that were built in many other places, it was also necessary to raise the price. The working hours also increased by 100 to 200 hours from the first drifter to the later ones, and the price increased from approx. DKK 700 to DKK 850. The last drifter, built in 1914, cost DKK 875 rig-ready. However, it was not so small an amount less than what German-built drifters amounted to. When the working time on a drifter was 800 to 1000 hours, and when the materials amounted to approx. half the price, grandfather’s prices can in no way be said to have been exorbitant. (See Appendix 1).

According to stored old accounts and papers, in the year 1895 in November a drifter was handed over to Jens Peter Jensen (“Degn”) on Askø. It was the third of grandfather’s later so well-known Fejøkvaser. In 1896 drifters were delivered in May, June and September, in 1897 in March, May and August, in 1898 in January, May and November, in 1899 in April. Occasionally, dinghies were built and keel hauling work was carried out at the harbor.

Grandfather could not always cope with the work as one man, but several times received help from house carpenter Rasmus Jørgensen and from the aforementioned Chr. Mortensen, until he started for himself with his own boatyard, also in Østerby. There has never been competition and disagreement between grandfather and him, and the families like to get together a few times during the winter for evening coffee. If grandfather could not cope with the demand for drifters, it was often that he referred to Chr. Mortensen, and his drifters were also very similar to his own. They also went to a forest auction together in the forest at Torrig on Lolland and sailed over there in grandfather’s little dinghy. It can be said that Chr. Mortensen and grandfather have helped to make their eel drifter fishery as widespread as it was, and that the Fejø drifter became known everywhere where eel fishing with drifters was practiced.

In the years up to 1914, a relatively large number of drifters were built in grandfather’s place in relation to its modest size, approx. 2-3 a year. In total, he built about 40 drifters (see the list above in appendix 2, as well as samples of the fishermen’s letters, appendix 3). Considering that occasional boats and dinghies were also built and repair work carried out in the harbor, it must be said that there was full employment at all times.

As a sideline, grandfather became harbor master in 1904 after Niels Christensen, the first harbor master. It was grandmother who in particular voted for him to take over this task, and she also kept accounts of the introduction of port fees and the collection of excise duty. In addition, she cared for the beacons, which were kerosene lamps until 1911, when the island got a power plant. Right up until her death in 1940, she kept the port accounts. Grandfather, and after his death father, arranged for the collection of the harbor dues and assigned the incoming ships their place in the harbor.

During the busy periods, Grandpa had various craftsmen to help, and in 1907 the eldest of the five children came home to help with the boat building. It was my father, Niels Carl Nielsen (called Carl Nielsen), who was born June 17, 1886. He had sailed since he was confirmed, first with small ships in freight, then with stone and wreck fishermen, and finally with steamships in North-Baltic shipping, on the Mediterranean, the West Indies and the North Atlantic.

In order not to be completely financially dependent on the boat building work, he paid for an old Nordenhuse boat set up so that it could be used for eel fishing as well as for herring fishing with drift nets. It was a boat that grandfather had bought, valued at 3 fathoms of firewood, when he built a drifter for fisherman Peter Olsen, Fejø in 1903. It had been lying on the meadow since no action had been taken to have it cut up. Now it got a lowered keel, got a new deck, coach roof forward, interior, well, new rigging and new sails. It was made as cheaply as possible outside working hours, but the boat was ready for the herring season in August and was named “Herring”. Father and two other fishermen, Carl Christensen and Julius Christensen, now fished together for a few years during the herring season, and they also fished quite well. At the same time, in the summer, the boat was used by the younger brothers for eel fishing. It was also used to pick up wood in the forests by Torrig, because then the freight for a boat skipper was saved, and when grandfather had to come anyway, it was also money to save. The trees were driven into the water by horse-drawn carriage. Small trees were loaded into the boat, while the larger logs, such as keel and bow trees, were tied up under the boat. In this way it was transported home to Fejø. The boat was first dismantled in the 1920s, so it came to do well after it had already been sentenced to dismantling in 1903.

In 1908, father had to go to war with “Herluf Trolle” from 18 May to 25 September. The rest of the year he worked at the naval shipyard and in the evenings received instruction in drawing and construction of ships from a master Bensen.

After returning home from the naval shipyard, until New Year 1909, he worked again with his father. When a skipper’s house next to the boatyard was for sale in 1911, Grandpa bought it and moved there. It was better by the road. When my father, after a long engagement, married my mother, Anna Marie Petersen, born on May 25, 1882 on Bornholm, on May 17, 1912, they moved into the old farmhouse for boat building. After a rebuilding in 1910, the old workshop was added to the farmhouse, so the new workshop was now completely outside this to the south. It had been given a floor area of 20-1/2 x 31 feet and it was furnished with skylights, which had been missed a lot in the old workshop. At the same time, another small piece of meadow had been bought, with beach rights and with right of use over the common meadow, almost so as not to lose the right of way across the meadow when the vessels were to be launched.

In 1910, the first motorboat was built by grandfather, namely a mail boat for postmaster Mikkelsen, Vejrø, to replace the old mail dinghy from 1880, which was now bought by postmaster Jensen, Fejø, and converted into a pleasure boat. The new mail boat cost 520 kr. It was built of oak so that it could withstand sailing, even if there was little ice coating on the water. It was approx. 20 feet long and equipped with a 3-horse hot-bulb engine (“Alpha”, Frederikshavn), and this gave the boat a speed of 5-1/2 knots. It was used as a mail boat without replacing the engine, until it was sold for other uses in the 1930s, when the Fejø-Vejrø postal route was closed down and replaced with a new Vejrø-Kragenæs route.

The largest boat ever built on the site was a 41 foot 5 inch long clinker-built oak cargo boat, “Viking II”, for one of grandfather’s sons, Ejler Nielsen. He came home after sailing for a few years and wanted to start in freight with a package route between Fejø and Nykøbing Falster. The route went well and was only completely stopped after the last world war. The boat was a good sailor, and since it was also equipped with an 8-horsepower “Dan” engine, it could easily maintain the route according to plan.

The last drifter was built in 1914, as the fishery had now also been expanded to fishing with herring drift nets. Several drifters had also been given an engine so that they could be used for otter-trawl fishing, which required the use of the vessel all year round. After the engine had become commonplace, it was no longer necessary to operate with the eel net; – a fishing method still in use. In addition, the keel-built boats were more usable, and they therefore switched to building such again. The piece that had been cut from the template in 1894, when grandfather started building the drifters, was therefore reattached, and the following boats were all built with keels.

The yacht is pulled out of the workshop before launch.

My grandfather, Christian Nielsen, died in March 1917 after working as a boat builder on Fejø first for a couple of years in the 1870s and then on this place from 1878. In the past 39 years he had built approx. 200 vessels of various sizes.

Boatbuilding after 1917

After my grandfather’s death, my father Carl Nielsen took over the boat building and at the same time the position as harbor master. He procured craftsman citizenship 7 Aug 1917. When grandfather died, a 28-foot boat was under construction for fisherman Viggo Nielsen, Onsevig. This and similar boats now took the place of the drifters, and during the following decade father built the following boats and larger dinghies:

| 1917 | 28.8 feet | boat for fisherman Viggo Nielsen, Onsevig (“Esther”). |

| 1917 | 25.7 feet | pilot boat for pilot Hansen, Femø |

| 1918 | 23.7 feet | pound net dinghy for fisherman J.P. Jensen, Askø (price DKK 650). |

| 1918 | 22.1 feet | pound net dinghy for fisherman Niels Nielsen (“Kulde”), Fejø (“Pax”). |

| 1919 | 27.8 feet | boat for fisherman Aksel Bang, Fejø (price DKK 1750) (“Christiane”). |

| 1920 | 30.9 feet | boat for fisherman Karl Gregersen, Lohals. |

| 1921 | 21.6 feet | pound net dinghy for fisherman Gregers Rasmussen, Askø. |

| 1923 | 23.7 feet | pilot boat for pilot Hans Hansen (Nagel), Rågø. |

| 1926 | 27.8 feet | boat for fisherman Marius Bang, Fejø (“Agnes”). |

fod = Danish foot = 0.314m

foot = imperial foot = 0.305m

Occasionally, small dinghies and barges were built, while engine work and other repair work were done. In 1928, a 22-foot pound net dinghy was built of oak, equipped with a 7-9 horsepower “Hejn” engine (Randers). The price was DKK 1,100 in rig-ready condition, with fittings. It was for fisherman Duval Jensen, Askø. In 1935, a 21-foot motorboat was delivered as a pilot boat to Oreby. In 1937, a 27-foot oak fishing boat (“Gerda”) was built for fisherman Duval Jensen, Askø. The boat was equipped with a 10-12 horsepower engine (“Hejn”, Randers). The price was rig-ready with fittings and painted DKK 2,500. In 1938, a 21-foot pilot dinghy was handed over to pilot Løje, Bandholm, equipped with an 8-horsepower “Solo” engine. In 1939, a special vessel of 23 feet was built according to the type of an old yacht, clinker-built of Kalmar wood, for engineer Knud E. Hansen, Espergærde; it was called “Solstraale”. In 1946, a clinker-built motorboat “Fri” was constructed of larch, 27 feet long and equipped with a 10 hp diesel engine, for the son, Chr. Nielsen, Fejø (author of this article). In 1948, a 28-foot fishing boat (“Vira”) was delivered, made of oak with a 20 hp diesel engine to fisherman Aksel Bang, Skalø. The boat cost 8500 DKK when finished, with engine work, and 1850 working hours were included. The oak for this alone cost DKK 2,500 in cut condition.

The number of new buildings in recent years is not as large as before, but from 1914 father has had work in the autumn for Sakskøbing sugar factory, first as a sampler and later as a weigher on Fejø from mid-September to Christmas. In 1920 he bought a band saw, and over the years he has cut a lot of firewood for the island’s inhabitants. Occasionally he made fruit boxes for the ever-growing fruit exports from Fejø. At the same time, there was not so little work with engine installation, first in older fishing boats and later, after the petrol engine had gained ground, in small dinghies. The work on this has taken up a lot of his time, and since there has also been relatively large repair work, as improvements were made, new decks were laid and several older fishing boats were made upright, there has been far from a shortage of work on the site.

In 1930, when the old workshop had also become fragile, a new one was built over the old one; it was built higher so that the boats could be built finished with a wheelhouse indoors, and the floor area was also slightly larger, namely 34 x 23-1/ 2 feet. Under the changing conditions, it has also done well.

The last boat was built by father in 1949, and now that he himself has come up well in years, he has not been interested in larger orders since then, but would rather have a little engine work and build a single smaller dinghy and some barges in between. Since 1917 he has built 16 boats and larger dinghies, 46 dinghies from 7 to 18 feet and approx. 75 barges from 10 to 18 feet. Despite his 75 years, he is still working and currently has orders for a few smaller dinghies and a barge.

Author’s postscript